PHAETON

Philippe Ledoux

First Issue: 1958

Catalogued: 4D

Dear Lily did it again and kindly lend me her beautiful, extensive research on this vintage jewel, thank you Lily, you are the best!

************************************************************************

Philippe Ledoux

First Issue: 1958

Catalogued: 4D

Dear Lily did it again and kindly lend me her beautiful, extensive research on this vintage jewel, thank you Lily, you are the best!

************************************************************************

I received my lovely Phaeton this week and couldn't resist doing a bit of research. (BkM this is especially for you and for shelby for her assistance in authenticating it!):

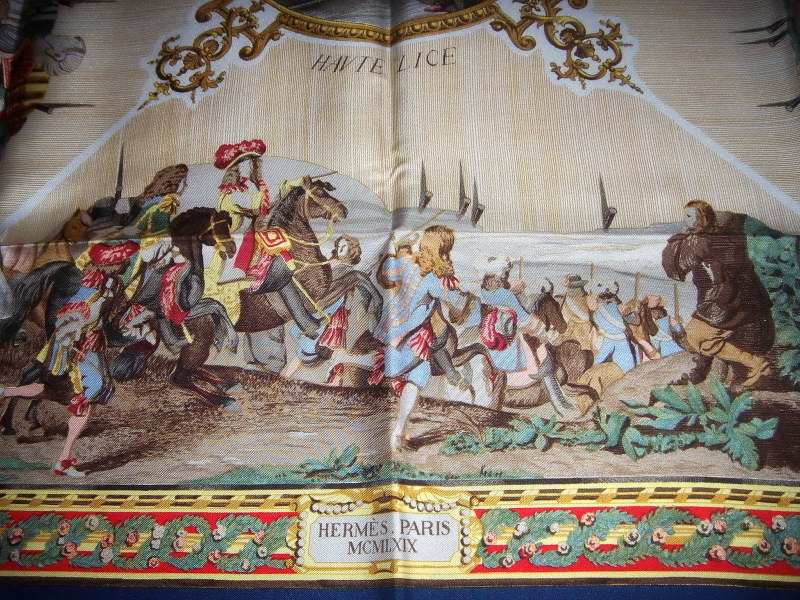

PHAETON – PHILIPPE LEDOUX (originally issued in 1958)

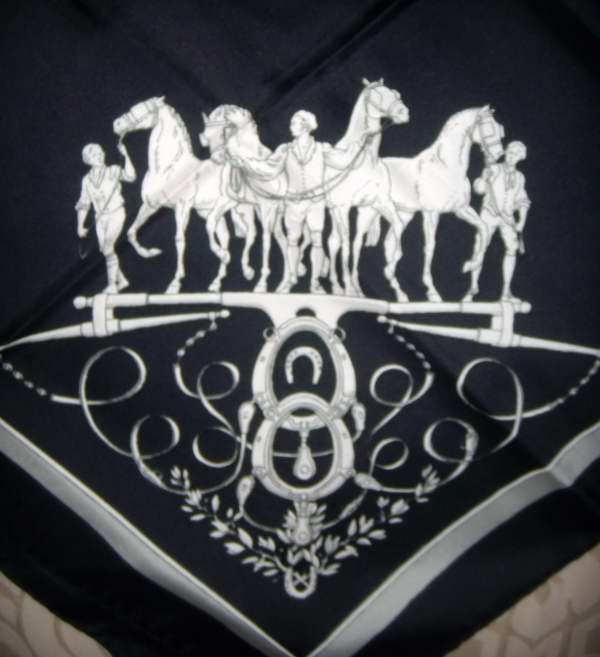

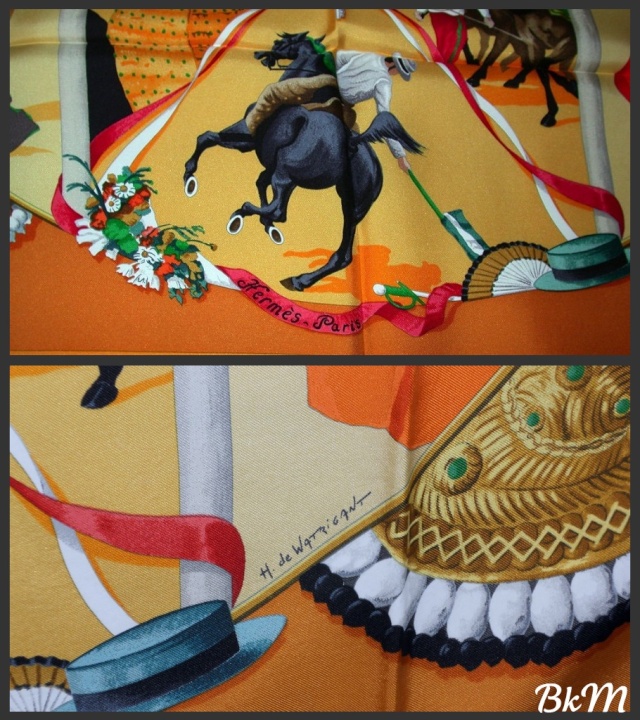

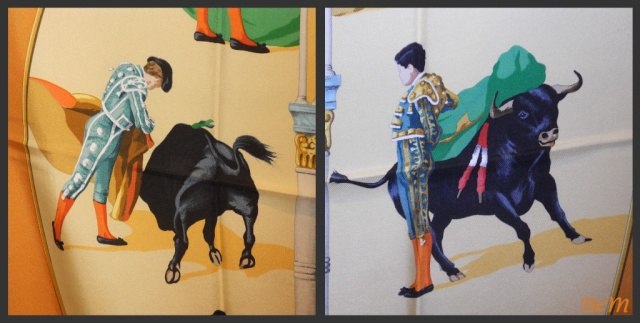

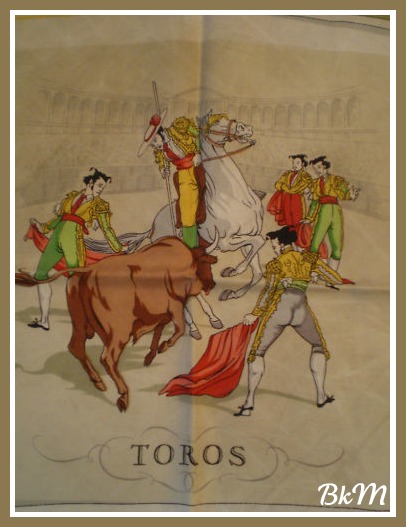

Any Hermes scarf collector, no doubt, is familiar with one of Hermes’ often used design motifs – the carriage. After all, it’s even part of their iconic Ex Libris logo. Ledoux seemed quite fond of the carriage, as well, and often incorporated various styles in his designs for Hermes.

The carriage in question here is a phaeton, from the Greek phaethon - to shine - and dates to the early 19th century when it was fashionable in France to use classical references (we’ll get to that a bit later.) In carriage speak, the phaeton was defined as a sporty open carriage, drawn by a single horse or a pair and was owner driven. Typically, it featured four extravagantly oversized wheels and was very lightly sprung with a minimal body. It was fast, and it was dangerous. It was also quite elegant, as one can see from the painting by George Stubbs below. Because of its speed and grace, the aristocracy adored it.

And, here we see the various phaetons depicted in Ledoux’s design:

But, there is so much more to this scarf than simply the haute monde out for a pleasant carriage ride on a lovely spring day in the Bois de Boulogne.

Phaeton also refers to the disastrous ride of Phaeton, the son of Helios (Apollo to the Romans) and the ocean goddess, Klymene (or Clymene, an Oceanid), who set the earth on fire in an attempt to drive the chariot of the sun. Phaeton was raised as the foster son of Merops, the King of Ethiopia, and one day his friend, Epaphus (the son of the king of Egypt) taunted him about his parentage.

“Son of Helios?” the other boy said. “A likely story. Your mother is ashamed to admit her liaison with some commoner, and so she claims a lofty lover who’s too

far away to deny it.”

Phaeton was distressed by his friend’s taunts and went to his mother, asking again about his true father. Even though she had told him many times, she told him once again:

“It is Helios. I swear by the River Styx, the dread river of the underworld on

which the gods of Olympus themselves swear binding oaths. Your father is

Helios, and if you doubt me, you can go to him yourself, for his halls are to the

east and not far from here.”

Delighted and relieved, Phaeton set out to seek his father’s house, following the directions provided by Klymene. His adventures in the eastern lands were many, but they are no longer remembered. In those days, there were no searing deserts but instead, lush gardens, verdant forests and shallow lakes. Still, he was wandering in wild lands, which according to Herodotus, were inhabited by strange and dangerous creatures. So, it took wile and courage to at last reach the Mountain of the Sun.

He declared himself at the gates, and servants led him up to his father’s great hall to await the chariot of Helios at day’s end.

Helios, when he descended the sky-track and found his son waiting in his halls, was very pleased that Phaeton had sought him out. He embraced the boy and affirmed Klymene’s words that he was, indeed, his true son. Moreover, Helios swore by the River Styx that we would grant Phaeton a wish – any one wish.

“Then let me drive your chariot, Father,” said Phaeton. "For then, no king's son will mock me as a bastard."

“Not that,” said Helios, in distress. “It is not safe for you, my son. The horses

that pull the Sun are fierce and wild. Only I may handle them. Ask me another

wish.”

“That is my wish,” Phaeton insisted. “Father, you promised.”

At this, Helios was distraught, for even the gods dared not break an oath sworn upon the Styx. At last, he gave in to his son’s pleas and led him to the stable shortly before dawn.

“Fly not too high,” Helios instructed him. “Nor too low. Keep to the zodiac.

That is the middle way.”

Then he put the whip in Phaeton’s hand and helped him into the chariot. He placed the golden helmet on Phaeton’s head, crowned him with his own fire, winding the seven rays like strings upon his hair and put the white tunic girdlewise over his loins, clothed him in own fiery robe and laced his foot into the purple boot. Overjoyed and proud, Phaeton took the reins with great joy and looking down, thanked his reluctant father for his gift.

Meanwhile, the four horses of Helios, Aethon (Blaze), Eous (Dawn), Pyrois (Fire), and Phelgon(Flame), kicked at the gates, anxious to be off on their daily journey.

The bronze doors of the east opened with a clang, and Phaeton stood tall in the chariot as the horses leapt into the sky. They vaulted upwards, red sparks clattering from their harnesses. At first all went well . . .

(“Phaeton & The Chariot of the Sun,” Athenian red-figure krater, 5th century BC, British Museum, London)

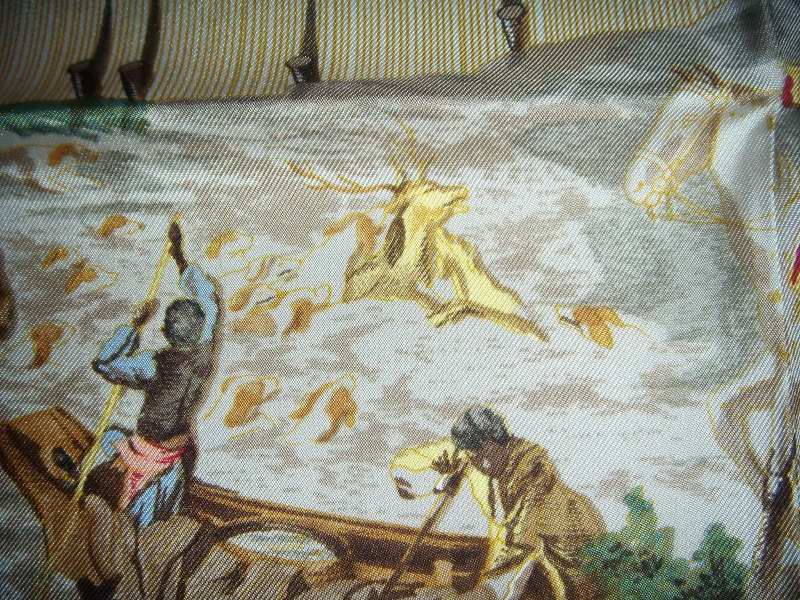

But Phaeton feared that his friend would not believe him unless he had some proof, so he tried to coax the horses to drop lower over Africa, so Epaphos might see him. The steeds fretted in their harness. His weight was lighter than his father’s, and the chariot was already swinging wildly from side to side. Abruptly, they bolted.

Down they plunged. The sun rattling behind them burned the lower air and set the forests ablaze. Rivers and lakes smoldered and dried up. The lands were parched to deserts, and the people living there were turned brown in the heat. Desperately, Phaeton tried to jerk the reins back and turn the horses upwards. They reared and raced heavenward, leaving the smoking earth behind. The lands below cracked under sheets of ice, and the sky itself began to burn, leaving a white scar in his wake – the Milky Way.

Phaeton drove harder still, drawing the chariot close to Notos (the South), to Boreas (the North), and close to Zephyros (the West) and then to Euros (the east.) With wonder, Luna (Selene, the Moon goddess) saw her brother’s team running wildly below her own. She sensed the impending disaster. There was tumult in the sky, shaking the core of the immovable universe. The very axle, which runs through the middle of the revolving heavens (and holds the constellations in their place) bent under the strain. Libyan Atlas (another son of Klymene) could hardly support the rolling firmament of stars, as he rested on his knees with back bowed under this great burden, and all the constellations and the stars were thrown from their paths in complete disarray.

As Phaeton looked down from this great height, he grew dizzy and ill. With the furious horses of fire running madly before him, he wished he had never set foot in his father’s chariot. But now the chariot was speeding head-long toward the gigantic Scorpion, and the huge monster raised its tail in an attempt to slash Phaeton with its stinger. Fear-struck, the boy dropped the reins completely, and the unchecked horses galloped downwards.

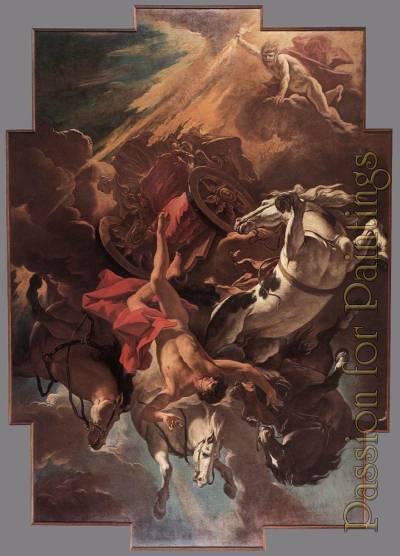

The horses bolted down, then up, then down again, burning and freezing the earth and sky. Zeus, the king of the gods, heard the cries from his suppliants, praying at the temples and looked out from Mt. Olympus. Seeing a stranger in Helios’ chariot, he launched a thunderbolt. There was deafening crash as the lightening shattered the chariot, and Phaeton fell wrapped in sizzling flames. The horses of the sun, now driverless, broke free of their harness, bolted and headed back to their stables on the Mountain of the Sun.

(“The Fall of Phaeton” Peter Paul Rubens, 1605)

(“Fall of Phaeton” by Sebastiano Ricci 1703/04)

The ill-fated Phaeton dropped like a falling star and plunged into the river Eridanos. His sisters, the Heliades, gathered on the banks of the river, and in their mourning were transformed into amber-teared poplar trees.

(“The Sisters of Phaeton” Tito di Santi for the Studiolo, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, 1572)

“Helios, mad with grief, his bright sheen subdued as in the gloom of an eclipse, loathing himself, the light, the day, gives way to his grief, and then with grief turning to rage denies his duty to the world.

'Enough,' he cries. 'Since time began my lot has brought no rest, no respite.

I resent this toil, unending toil, unhonoured drudgery. Let someone else take out

my chariot that bears my sunbeams, or if no one will, and all the gods confess they can’t, let Jove (Zeus) drive it, and as he wrestles with the reins,

there’ll be a while at least when he won’t wield his bolt to rob a father of his son; and when he’s tried the fiery-footed team and learnt their strength, he’ll know no one should die for failing to control them expertly.'

Then, all the deities surround Helios and beg and beseech him not to shroud

the world in darkness. Zeus, indeed, defends his fiery bolt and adds his royal

threats. So Helios took in hand his maddened team, still terrified, and whipped them savagely, whipped them and cursed them for their guilt that they destroyed his son, their master that dire day.” (Ovid – “Metamorphoses)

After his death, Phaeton was placed among the stars as the constellation Auriga (the charioteer), or else transformed into the god of the star the Greeks called Phaeton – the planet Jupiter or Saturn.

His devoted friend (some claim lover), Kyknos, who dove repeatedly into the river Eridanos, attempting to retrieve his body, was turned into a swan (a bird sacred to Helios) by the gods in an attempt to relieve his grief. (You can see his swan’s image in “The Sisters of Phaeton” above.)

Ledoux’s portrayal of the doomed youth, Phaeton and the centerpiece of the scarf:

Obviously, he’s chosen to portray the ill-fated Phaeton prior to his disastrous destiny and fiery death. He is still in control of the horses of the sun at this point, but, sadly, we know the fate that awaits him.

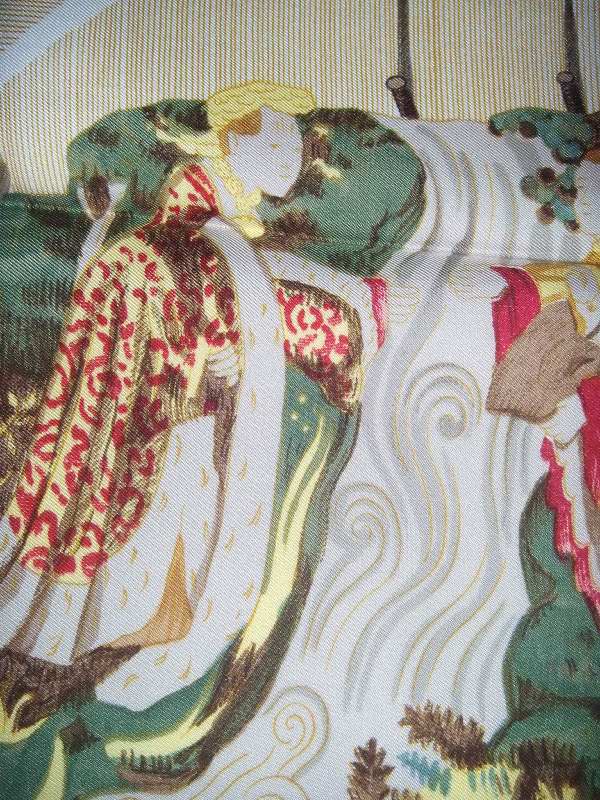

And, in closing, two of the four lovely corner details - much more docile horses, who, no doubt, would be happy to pull a phaeton through a Paris park on a tranquil day and avoid the fate of Phaeton and his ferocious team.