Dear vintage lovers, I have decided to discontinue the review on Hubert de Watrigant for the time being, the reason is that my dear friend Lily has made the most beautiful review on a vintage treasure, Haute Lice by Ledoux from 1969 and she has been kind and generous enough to allow me to post her wonderful work, read and enjoy!

*******************************

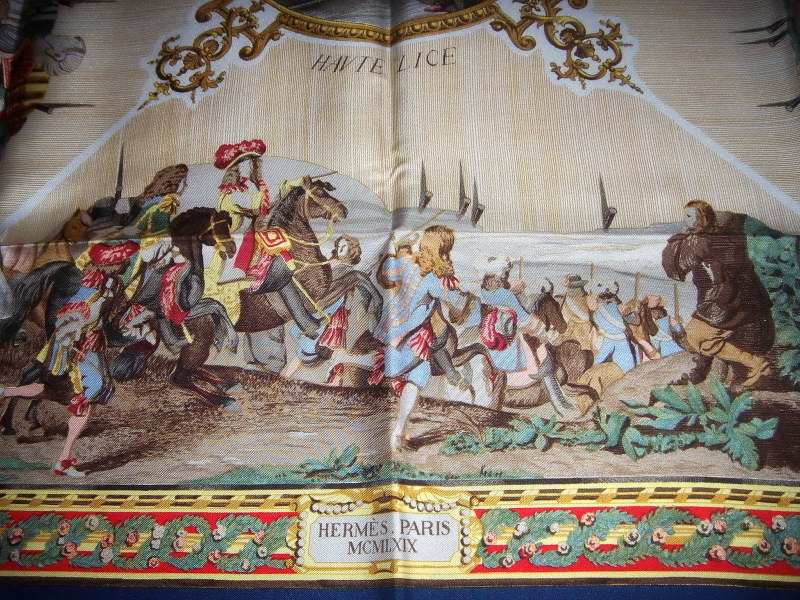

HAUTE LICE 1969

Philippe Ledoux

Catalogued: 3C

Another wonderful look into the past, compliments of Hermes and artist, Philippe Ledoux.

Haute Lice (pronounced ho-t-li-s) translates to high warp and applies to the process of weaving rather than to a tapestry itself.

In the haute lice manner, the warp is vertical, and the weaver stands behind it while weaving in the figures (or the woof). In the opposite method, basse lice (low warp), the warp is horizontal, and the weaver works in the pattern from above. In the haute lice method, he works from the wrong side of the tapestry (but in the basse lice, it is worked from the right side.) The work of the former method is slower, more difficult and, therefore, more expensive to produce and is considered of a “higher order.”

These tapestries, which were used as elaborate wall and floor coverings, have their beginnings in the Middle Ages, and the most famous were known as the “Tapestries of Arras,” which were worked exclusively in the high warp method – haute lice - and often included the addition of gold or metallic threads.

From Les Tapis de Haute-Lice (Galerie Girard, Lyon, France, which still produces these tapestries today, worked on a high warp):

“It was during the Crusades that Europeans discovered “hairy” carpets in the Near East. The Europeans endeavored to create their own versions and to compensate for economic losses sustained as a result of importations.

From the early 17th century, orientalizing styles are superseded by carpets from the Savonnerie Workshops (cotton is used for both the warp and the woof), and in the 18th century, by those of Aubusson and Beauvais (a combination of cotton used for the warp and wool and/or silk velvet for the woof). As status symbols and statements of good taste, these carpets were for the privileged kings and gentry, but they spread throughout Europe and the West: Spain in the Golden Age; Great Britain and its Moorfields, Exeter and Axminster carpets; America, Eastern Europe, Ireland, Scotland, Austria, the Netherlands and its Deventer workshops; Tournai in Belgium, etc. And in the last two centuries, designs by William Morris, Walter Grane, Charles Mackintosh, V. Horta, J. Olbrich, Frank Lloyd Wright, Sonia Delaunay, Picasso, Starck, Hockney and Harding.

Towards the end of the 20th century, the Aubusson workshops, the last great manufacturers, experienced ever greater difficulty producing and, even more so, selling the last Savonneries, as the cost of labor in the West had priced them out of the market. The last entrepreneurs “burned their boats,” setting up shop where labor was plentiful, qualified, inexpensive and skilled in the old ways.

Very few would succeed. Indeed, only those who already had the know-how in Aubusson technique and who settled in the very area where the most amazing textiles of the ancient world had been in production for quite some time with the enduring legacy of the masters of silk managed to succeed.”

And now – to the scarf.

In Ledoux’s little masterpiece, we see the artisan or licier at work on his high warp frame in the center of the scarf, and he closely resembles this drawing I found. He’s working from the wrong side of the tapestry, and you can see the various shuttles hanging from the weaving he’s completed, each of which used to weave a different color into the woof.

The center ground is a representation of the actual cotton warp – the basis and foundation for the weaving, and the four border panels represent various tapestries in production. I can’t identify them, but I would imagine that an historical tapestry expert could, as I’m sure that Ledoux probably used famous examples as his inspiration. Interestingly enough, Ledoux also incorporated the actual date of the design in Roman numerals in the center plaque - 1969.

Panel I at the bottom is an historical battle scene, perhaps? The figures seem to be running into battle with lances drawn.

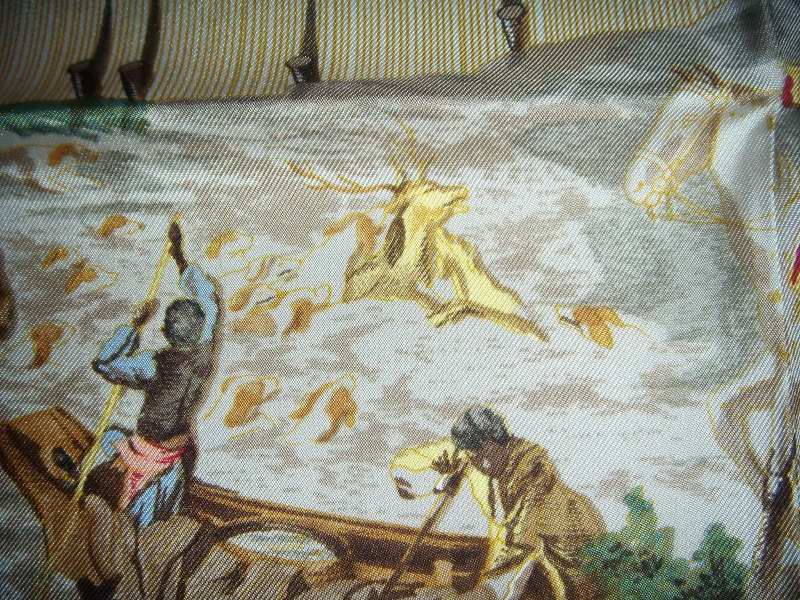

The right panel represents a hunt scene, and a rather violent one at that. Hounds have chased an unfortunate stag into a river, and one is leaping at the stag’s throat, while another pack of hounds bays on the riverbank, and huntsmen blow their horns, encouraging the dogs on. Servants push off the bank in a dugout boat, probably to transport the bloody prize back to their lords, who eagerly await a feast of fresh venison.

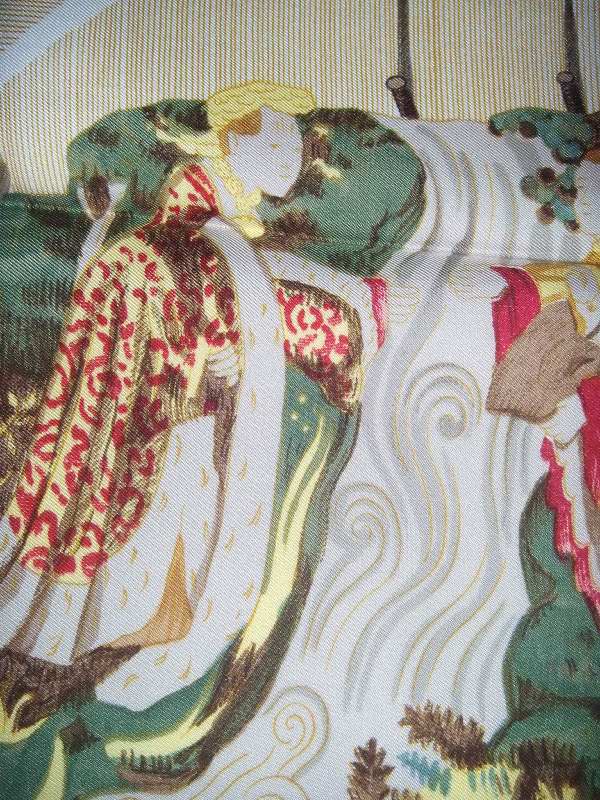

The top panel is, fortunately, a much more pleasant - a peaceful scene of noblemen and their ladies enjoying a day in the country. One beautifully attired lady plays a harp, while her gentleman friend obligingly holds the music scroll for her, and another gallant offers his hand to a lady in an ermine-trimmed gown, attempting to cross a fast moving stream.

(It’s interesting to note that the costumes in this panel and the left panel appear to be Medieval or Renaissance era, while those in the bottom and right panels look to be more period 17th-18th century dress.)

The left panel is my favorite of the four. The work in progress seems to be Neoclassical in theme due to the Greek temple with Doric columns in the background.

To the right, we see the proprietress of the workshop accepting payment for the work in progress (an installment plan, no doubt.) She already has a sizable pile of gold coins under her left hand, but she has managed to extract one more from the nobleman’s purse, which rests on her counter. From the look on his face, he seems to be a bit dismayed by the process, akin to a modern day DH paying at Hermes, no doubt!

I’m puzzled by the four figures in the various corners. At first, I thought they were probably famous artisans of the time, but the two in the lower bottom corners seem to be classical sculptures – a boy with a dog jumping at his side and in the opposite corner, a womanly figure, holding a crown in her hand, with a putto, or maybe just a child, at her side and a swan at her feet on the left. Perhaps she is an allegory for Mother France or possibly a reference to the famous Leda of Greek myth.

However, I'm leaning towards the Leda myth. Notice the putti, particularly the one bearing the crown in the first painting below.)

The two female figures in the top corners appear to be in medieval costume. The one in the upper right is expecting, holding her hand over her pregnant stomach. Perhaps they are patrons or artisans themselves. Unfortunately, they remain a puzzle to me.

What doesn't puzzle me, however, is the beauty and artistry, as well as the historical detail of this scarf. Ledoux continues to amaze me! He is truly a stellar example of Hermes at its zenith.