Wednesday, January 12, 2011

PHILIPPE LEDOUX I Napoleon 1963

NAPOLEON

Philippe Ledoux

Jacquard silk

First Issue: 1963

Reissues: 1985, 1995

Catalogued: 5D

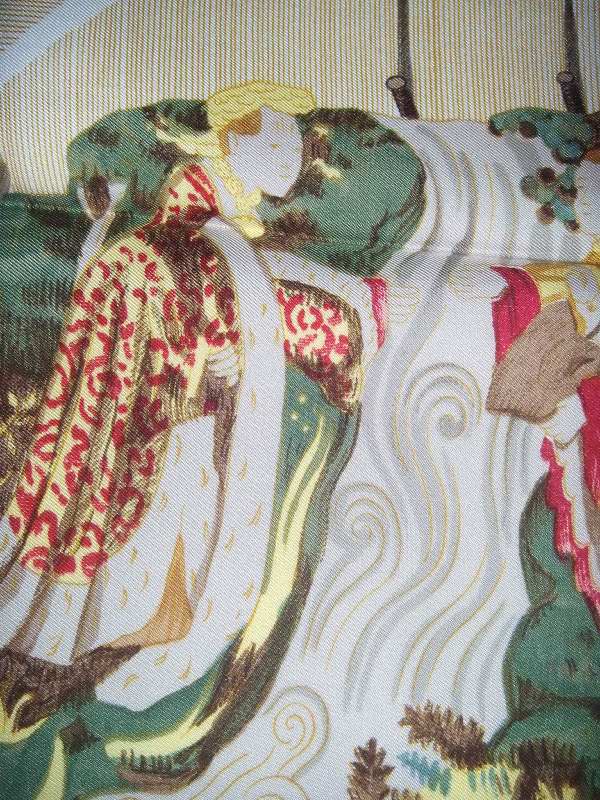

This is my beautiful Napoleon by Philippe Ledoux:

(Este es mi precioso Napoleón por Philippe Ledoux:)

A detail of the central motive, the colors are incredible, antique green and burgundy, you could almost feel the touch of ancient velvet!!!

(Un detalle del motivo central, los colores son increíbles, verde antiguo y granate, casi puedes notar el tacto de viejo terciopelo:)

Philippe Ledoux made an extraordinary research when designing Napoleon, all four the corners are inspired on different paintings of the historical figure:

(Philippe Ledoux hizo una extraordinaria investigación cuando diseñó Napoleón, las cuatro esquinas están inspiradas en diferentes retratos de la figura histórica:)

Napoleon was wounded in Rattisbone:

(Napoleón herido en Ratisbona:)

This is the original painting by Pierre Gautherot:

(Esta es la pintura original de Pierre Gautherot)

The upper left corner is the most easy to recognize as it's based on a famous painting by JL.David depicting the Pass of St.Bernard:

(La esquina superior izquierda es la más fácil de reconocer porque está basada en una famosa pintura de JL David que muestra el Paso de San Bernard)

Original painting:

(Pintura original:)

The last corner (upper right) is the trickiest to recognize, it represents Napoleon proclaimed Premier Consul:

(La última esquina (superior derecha) es la más difícil de reconocer, representa a Napoleón proclamado Primer Consul:)

Ledoux got his inspiration from a tapestry, Tapisserie des Gobelins:

Ledoux encontró su inspiración en un tapiz de Tapicería de los Gobelinos:

At the center of the scarf, Ledoux depicts the arrival at Notre Dame Dec 2, 1804 after burning the Book of Rites:

En el centro del pañuelo, Ledoux representa la llegada a Notre Dame el 2 de diciembre de 1804 después de quemar el Libro de los Ritos:

Symbols and arms in Napoleon:

The Bees: the golden bees called cicadas, are symbol of immortality and resurrection, they were chosen to link the new dynasty to the very origins of France as cicadas were discovered in the tomb of Childeric I, founder of Merovingian dynasty in 457. Bees are the oldest symbol for French monarchy.

The uniforms in the center, the swords: on the left there is the First Consul dresscoat, on the right, Napoleon's Chasseurs à Cheval uniform. Further down the design, the First Consul and Coronation swords can be seen, as well as two sabres from the Egyptian campaign.

The chain of the Légion d'honneur: it took its name from ancient Rome. The chain of the Légion d'honneur, reserved for the emperor, princes of the imperial family and grand dignitaries, is composed of a gold chain made of 16 trophies linked by eagles with the ribbon and cross of the order at their necks. This chain is bordered on either side by a small chain alternating stars and bees. The central motif, the Napoleonic N, is encircled by a laurel wreath and supports the cross of the Légion d'honneur, a five-pointed pommel-pointed star, in white enamel. In the centre is the laurel-crowned profile of the emperor, the whole surmounted by the imperial crown.

The Eagle: it's a symbol of imperial Rome, Jupiter's bird, and was associated from the earliest antiquity with military victory. The day after his coronation, Napoleon had an eagle placed at the top of the shaft of every flag in the Napoleonic army.

I've tried to discover the real meaning of the number 25 displayed four times on the scarf. I should think that it has something to do with freemasonry, 25 is a powerful number for old freemasons and it's possible that Ledoux belonged to some of this societies in France as Napoleon did.

Napoleon is a jacquard silk scarf, for more information about jacquard technique in Hermès scarves, please visit the following link:

Napoleón es un pañuelo en jacquard de seda, para más información sobre está técnica en Hermès, por favor, visita el siguiente link:

*******************************************

PHILIPPE LEDOUX II La Comedie Italienne 1962

LA COMEDIE ITALIENNE

Philippe Ledoux

Jacquard silk

First Issue: 1962

Catalogued: 2C

Zanni (servants) Colombina, Pulcinella, Arlecchino, Crispin, Brigbela and Mezzetin (brothers), Scaramouche, Bellosguardo, Scarpin, Pierrot.

Philippe Ledoux

Jacquard silk

First Issue: 1962

Catalogued: 2C

Let me introduce the beautiful vintage jacquard scarf La Comedie Italienne by Philippe Ledoux in 1962.

It’s based on La Commedia dell’Arte, a form of theatre that began in Italy in the mid-16th century, characterized by masked "types", the advent of the actress and improvised performances based on sketches or scenarios.

The classic, traditional plot is that the innamorati are in love and wish to be married, but one elder, vecchio, or several elders, vecchi, prevent this from happening, leading the lovers to ask one or more zanni (eccentric servants) for help. Typically, the story ends happily with the marriage of the innamorati and forgiveness for any wrongdoings.

Please, watch the details, landscapes, backgrounds and expressions, this is one of the best Hermes scarves ever!

Zanni (servants) Colombina, Pulcinella, Arlecchino, Crispin, Brigbela and Mezzetin (brothers), Scaramouche, Bellosguardo, Scarpin, Pierrot.

Friday, February 11, 2011

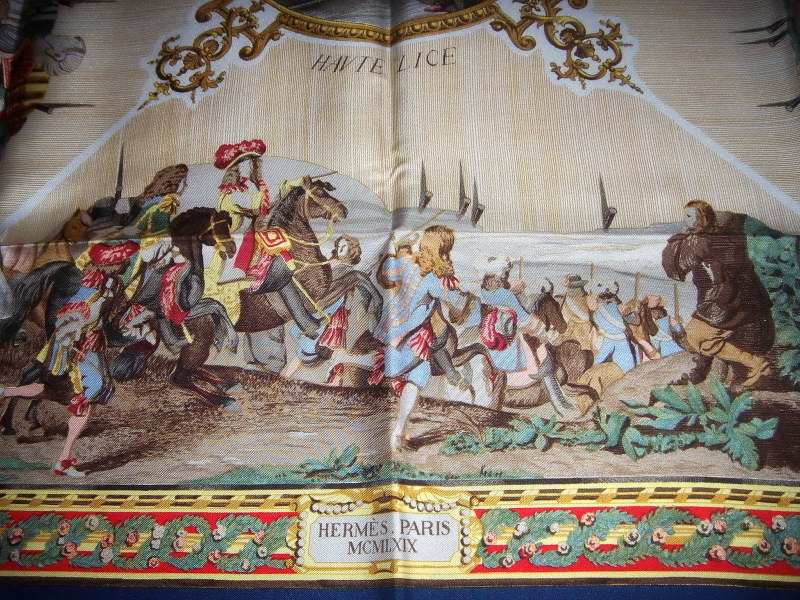

PHILIPPE LEDOUX III Haute Lice 1969

Dear vintage lovers, I have decided to discontinue the review on Hubert de Watrigant for the time being, the reason is that my dear friend Lily has made the most beautiful review on a vintage treasure, Haute Lice by Ledoux from 1969 and she has been kind and generous enough to allow me to post her wonderful work, read and enjoy!

*******************************

HAUTE LICE 1969

Philippe Ledoux

Catalogued: 3C

Another wonderful look into the past, compliments of Hermes and artist, Philippe Ledoux.

Haute Lice (pronounced ho-t-li-s) translates to high warp and applies to the process of weaving rather than to a tapestry itself.

In the haute lice manner, the warp is vertical, and the weaver stands behind it while weaving in the figures (or the woof). In the opposite method, basse lice (low warp), the warp is horizontal, and the weaver works in the pattern from above. In the haute lice method, he works from the wrong side of the tapestry (but in the basse lice, it is worked from the right side.) The work of the former method is slower, more difficult and, therefore, more expensive to produce and is considered of a “higher order.”

These tapestries, which were used as elaborate wall and floor coverings, have their beginnings in the Middle Ages, and the most famous were known as the “Tapestries of Arras,” which were worked exclusively in the high warp method – haute lice - and often included the addition of gold or metallic threads.

From Les Tapis de Haute-Lice (Galerie Girard, Lyon, France, which still produces these tapestries today, worked on a high warp):

“It was during the Crusades that Europeans discovered “hairy” carpets in the Near East. The Europeans endeavored to create their own versions and to compensate for economic losses sustained as a result of importations.

From the early 17th century, orientalizing styles are superseded by carpets from the Savonnerie Workshops (cotton is used for both the warp and the woof), and in the 18th century, by those of Aubusson and Beauvais (a combination of cotton used for the warp and wool and/or silk velvet for the woof). As status symbols and statements of good taste, these carpets were for the privileged kings and gentry, but they spread throughout Europe and the West: Spain in the Golden Age; Great Britain and its Moorfields, Exeter and Axminster carpets; America, Eastern Europe, Ireland, Scotland, Austria, the Netherlands and its Deventer workshops; Tournai in Belgium, etc. And in the last two centuries, designs by William Morris, Walter Grane, Charles Mackintosh, V. Horta, J. Olbrich, Frank Lloyd Wright, Sonia Delaunay, Picasso, Starck, Hockney and Harding.

Towards the end of the 20th century, the Aubusson workshops, the last great manufacturers, experienced ever greater difficulty producing and, even more so, selling the last Savonneries, as the cost of labor in the West had priced them out of the market. The last entrepreneurs “burned their boats,” setting up shop where labor was plentiful, qualified, inexpensive and skilled in the old ways.

Very few would succeed. Indeed, only those who already had the know-how in Aubusson technique and who settled in the very area where the most amazing textiles of the ancient world had been in production for quite some time with the enduring legacy of the masters of silk managed to succeed.”

And now – to the scarf.

In Ledoux’s little masterpiece, we see the artisan or licier at work on his high warp frame in the center of the scarf, and he closely resembles this drawing I found. He’s working from the wrong side of the tapestry, and you can see the various shuttles hanging from the weaving he’s completed, each of which used to weave a different color into the woof.

The center ground is a representation of the actual cotton warp – the basis and foundation for the weaving, and the four border panels represent various tapestries in production. I can’t identify them, but I would imagine that an historical tapestry expert could, as I’m sure that Ledoux probably used famous examples as his inspiration. Interestingly enough, Ledoux also incorporated the actual date of the design in Roman numerals in the center plaque - 1969.

Panel I at the bottom is an historical battle scene, perhaps? The figures seem to be running into battle with lances drawn.

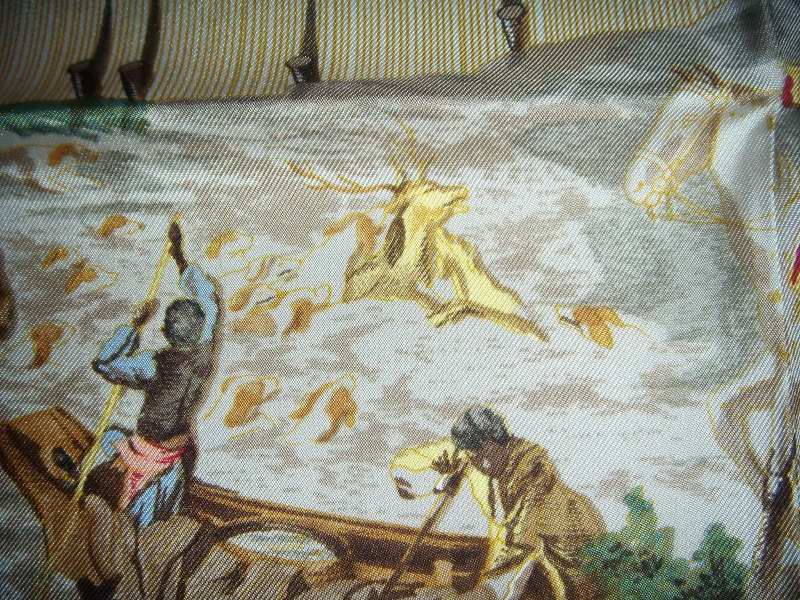

The right panel represents a hunt scene, and a rather violent one at that. Hounds have chased an unfortunate stag into a river, and one is leaping at the stag’s throat, while another pack of hounds bays on the riverbank, and huntsmen blow their horns, encouraging the dogs on. Servants push off the bank in a dugout boat, probably to transport the bloody prize back to their lords, who eagerly await a feast of fresh venison.

The top panel is, fortunately, a much more pleasant - a peaceful scene of noblemen and their ladies enjoying a day in the country. One beautifully attired lady plays a harp, while her gentleman friend obligingly holds the music scroll for her, and another gallant offers his hand to a lady in an ermine-trimmed gown, attempting to cross a fast moving stream.

(It’s interesting to note that the costumes in this panel and the left panel appear to be Medieval or Renaissance era, while those in the bottom and right panels look to be more period 17th-18th century dress.)

The left panel is my favorite of the four. The work in progress seems to be Neoclassical in theme due to the Greek temple with Doric columns in the background.

To the right, we see the proprietress of the workshop accepting payment for the work in progress (an installment plan, no doubt.) She already has a sizable pile of gold coins under her left hand, but she has managed to extract one more from the nobleman’s purse, which rests on her counter. From the look on his face, he seems to be a bit dismayed by the process, akin to a modern day DH paying at Hermes, no doubt!

I’m puzzled by the four figures in the various corners. At first, I thought they were probably famous artisans of the time, but the two in the lower bottom corners seem to be classical sculptures – a boy with a dog jumping at his side and in the opposite corner, a womanly figure, holding a crown in her hand, with a putto, or maybe just a child, at her side and a swan at her feet on the left. Perhaps she is an allegory for Mother France or possibly a reference to the famous Leda of Greek myth.

However, I'm leaning towards the Leda myth. Notice the putti, particularly the one bearing the crown in the first painting below.)

The two female figures in the top corners appear to be in medieval costume. The one in the upper right is expecting, holding her hand over her pregnant stomach. Perhaps they are patrons or artisans themselves. Unfortunately, they remain a puzzle to me.

What doesn't puzzle me, however, is the beauty and artistry, as well as the historical detail of this scarf. Ledoux continues to amaze me! He is truly a stellar example of Hermes at its zenith.

*****************************************************

Monday, February 28, 2011

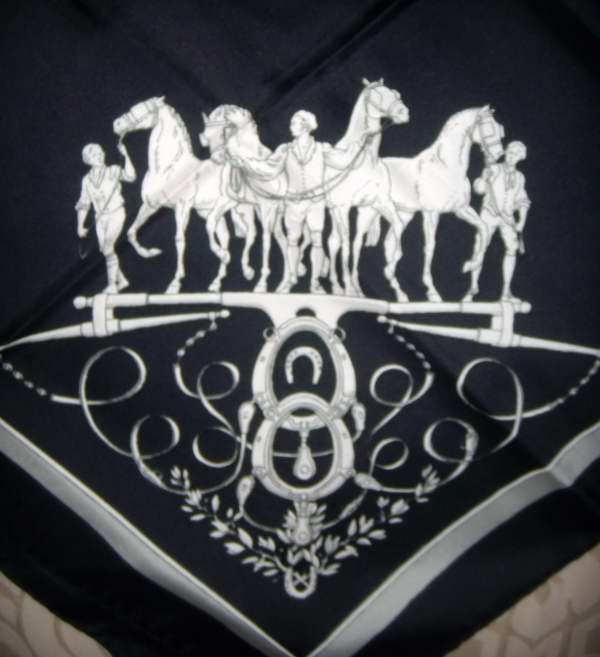

PHILIPPE LEDOUX IV Phaeton 1958

PHAETON

Philippe Ledoux

First Issue: 1958

Catalogued: 4D

Dear Lily did it again and kindly lend me her beautiful, extensive research on this vintage jewel, thank you Lily, you are the best!

************************************************************************

Philippe Ledoux

First Issue: 1958

Catalogued: 4D

Dear Lily did it again and kindly lend me her beautiful, extensive research on this vintage jewel, thank you Lily, you are the best!

************************************************************************

I received my lovely Phaeton this week and couldn't resist doing a bit of research. (BkM this is especially for you and for shelby for her assistance in authenticating it!):

PHAETON – PHILIPPE LEDOUX (originally issued in 1958)

Any Hermes scarf collector, no doubt, is familiar with one of Hermes’ often used design motifs – the carriage. After all, it’s even part of their iconic Ex Libris logo. Ledoux seemed quite fond of the carriage, as well, and often incorporated various styles in his designs for Hermes.

The carriage in question here is a phaeton, from the Greek phaethon - to shine - and dates to the early 19th century when it was fashionable in France to use classical references (we’ll get to that a bit later.) In carriage speak, the phaeton was defined as a sporty open carriage, drawn by a single horse or a pair and was owner driven. Typically, it featured four extravagantly oversized wheels and was very lightly sprung with a minimal body. It was fast, and it was dangerous. It was also quite elegant, as one can see from the painting by George Stubbs below. Because of its speed and grace, the aristocracy adored it.

And, here we see the various phaetons depicted in Ledoux’s design:

But, there is so much more to this scarf than simply the haute monde out for a pleasant carriage ride on a lovely spring day in the Bois de Boulogne.

Phaeton also refers to the disastrous ride of Phaeton, the son of Helios (Apollo to the Romans) and the ocean goddess, Klymene (or Clymene, an Oceanid), who set the earth on fire in an attempt to drive the chariot of the sun. Phaeton was raised as the foster son of Merops, the King of Ethiopia, and one day his friend, Epaphus (the son of the king of Egypt) taunted him about his parentage.

“Son of Helios?” the other boy said. “A likely story. Your mother is ashamed to admit her liaison with some commoner, and so she claims a lofty lover who’s too

far away to deny it.”

Phaeton was distressed by his friend’s taunts and went to his mother, asking again about his true father. Even though she had told him many times, she told him once again:

“It is Helios. I swear by the River Styx, the dread river of the underworld on

which the gods of Olympus themselves swear binding oaths. Your father is

Helios, and if you doubt me, you can go to him yourself, for his halls are to the

east and not far from here.”

Delighted and relieved, Phaeton set out to seek his father’s house, following the directions provided by Klymene. His adventures in the eastern lands were many, but they are no longer remembered. In those days, there were no searing deserts but instead, lush gardens, verdant forests and shallow lakes. Still, he was wandering in wild lands, which according to Herodotus, were inhabited by strange and dangerous creatures. So, it took wile and courage to at last reach the Mountain of the Sun.

He declared himself at the gates, and servants led him up to his father’s great hall to await the chariot of Helios at day’s end.

Helios, when he descended the sky-track and found his son waiting in his halls, was very pleased that Phaeton had sought him out. He embraced the boy and affirmed Klymene’s words that he was, indeed, his true son. Moreover, Helios swore by the River Styx that we would grant Phaeton a wish – any one wish.

“Then let me drive your chariot, Father,” said Phaeton. "For then, no king's son will mock me as a bastard."

“Not that,” said Helios, in distress. “It is not safe for you, my son. The horses

that pull the Sun are fierce and wild. Only I may handle them. Ask me another

wish.”

“That is my wish,” Phaeton insisted. “Father, you promised.”

At this, Helios was distraught, for even the gods dared not break an oath sworn upon the Styx. At last, he gave in to his son’s pleas and led him to the stable shortly before dawn.

“Fly not too high,” Helios instructed him. “Nor too low. Keep to the zodiac.

That is the middle way.”

Then he put the whip in Phaeton’s hand and helped him into the chariot. He placed the golden helmet on Phaeton’s head, crowned him with his own fire, winding the seven rays like strings upon his hair and put the white tunic girdlewise over his loins, clothed him in own fiery robe and laced his foot into the purple boot. Overjoyed and proud, Phaeton took the reins with great joy and looking down, thanked his reluctant father for his gift.

Meanwhile, the four horses of Helios, Aethon (Blaze), Eous (Dawn), Pyrois (Fire), and Phelgon(Flame), kicked at the gates, anxious to be off on their daily journey.

The bronze doors of the east opened with a clang, and Phaeton stood tall in the chariot as the horses leapt into the sky. They vaulted upwards, red sparks clattering from their harnesses. At first all went well . . .

(“Phaeton & The Chariot of the Sun,” Athenian red-figure krater, 5th century BC, British Museum, London)

But Phaeton feared that his friend would not believe him unless he had some proof, so he tried to coax the horses to drop lower over Africa, so Epaphos might see him. The steeds fretted in their harness. His weight was lighter than his father’s, and the chariot was already swinging wildly from side to side. Abruptly, they bolted.

Down they plunged. The sun rattling behind them burned the lower air and set the forests ablaze. Rivers and lakes smoldered and dried up. The lands were parched to deserts, and the people living there were turned brown in the heat. Desperately, Phaeton tried to jerk the reins back and turn the horses upwards. They reared and raced heavenward, leaving the smoking earth behind. The lands below cracked under sheets of ice, and the sky itself began to burn, leaving a white scar in his wake – the Milky Way.

Phaeton drove harder still, drawing the chariot close to Notos (the South), to Boreas (the North), and close to Zephyros (the West) and then to Euros (the east.) With wonder, Luna (Selene, the Moon goddess) saw her brother’s team running wildly below her own. She sensed the impending disaster. There was tumult in the sky, shaking the core of the immovable universe. The very axle, which runs through the middle of the revolving heavens (and holds the constellations in their place) bent under the strain. Libyan Atlas (another son of Klymene) could hardly support the rolling firmament of stars, as he rested on his knees with back bowed under this great burden, and all the constellations and the stars were thrown from their paths in complete disarray.

As Phaeton looked down from this great height, he grew dizzy and ill. With the furious horses of fire running madly before him, he wished he had never set foot in his father’s chariot. But now the chariot was speeding head-long toward the gigantic Scorpion, and the huge monster raised its tail in an attempt to slash Phaeton with its stinger. Fear-struck, the boy dropped the reins completely, and the unchecked horses galloped downwards.

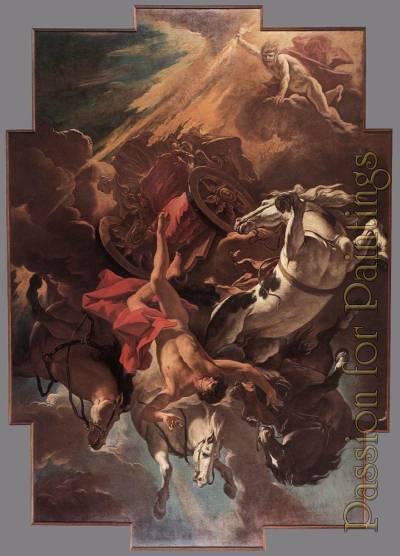

The horses bolted down, then up, then down again, burning and freezing the earth and sky. Zeus, the king of the gods, heard the cries from his suppliants, praying at the temples and looked out from Mt. Olympus. Seeing a stranger in Helios’ chariot, he launched a thunderbolt. There was deafening crash as the lightening shattered the chariot, and Phaeton fell wrapped in sizzling flames. The horses of the sun, now driverless, broke free of their harness, bolted and headed back to their stables on the Mountain of the Sun.

(“The Fall of Phaeton” Peter Paul Rubens, 1605)

(“Fall of Phaeton” by Sebastiano Ricci 1703/04)

The ill-fated Phaeton dropped like a falling star and plunged into the river Eridanos. His sisters, the Heliades, gathered on the banks of the river, and in their mourning were transformed into amber-teared poplar trees.

(“The Sisters of Phaeton” Tito di Santi for the Studiolo, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, 1572)

“Helios, mad with grief, his bright sheen subdued as in the gloom of an eclipse, loathing himself, the light, the day, gives way to his grief, and then with grief turning to rage denies his duty to the world.

'Enough,' he cries. 'Since time began my lot has brought no rest, no respite.

I resent this toil, unending toil, unhonoured drudgery. Let someone else take out

my chariot that bears my sunbeams, or if no one will, and all the gods confess they can’t, let Jove (Zeus) drive it, and as he wrestles with the reins,

there’ll be a while at least when he won’t wield his bolt to rob a father of his son; and when he’s tried the fiery-footed team and learnt their strength, he’ll know no one should die for failing to control them expertly.'

Then, all the deities surround Helios and beg and beseech him not to shroud

the world in darkness. Zeus, indeed, defends his fiery bolt and adds his royal

threats. So Helios took in hand his maddened team, still terrified, and whipped them savagely, whipped them and cursed them for their guilt that they destroyed his son, their master that dire day.” (Ovid – “Metamorphoses)

After his death, Phaeton was placed among the stars as the constellation Auriga (the charioteer), or else transformed into the god of the star the Greeks called Phaeton – the planet Jupiter or Saturn.

His devoted friend (some claim lover), Kyknos, who dove repeatedly into the river Eridanos, attempting to retrieve his body, was turned into a swan (a bird sacred to Helios) by the gods in an attempt to relieve his grief. (You can see his swan’s image in “The Sisters of Phaeton” above.)

Ledoux’s portrayal of the doomed youth, Phaeton and the centerpiece of the scarf:

Obviously, he’s chosen to portray the ill-fated Phaeton prior to his disastrous destiny and fiery death. He is still in control of the horses of the sun at this point, but, sadly, we know the fate that awaits him.

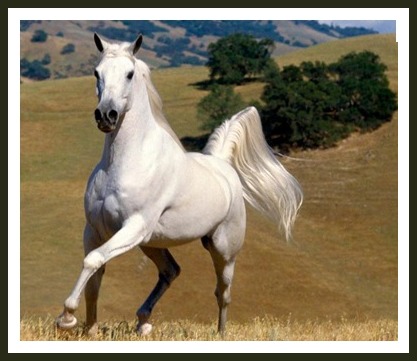

And, in closing, two of the four lovely corner details - much more docile horses, who, no doubt, would be happy to pull a phaeton through a Paris park on a tranquil day and avoid the fate of Phaeton and his ferocious team.

*******************************************

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

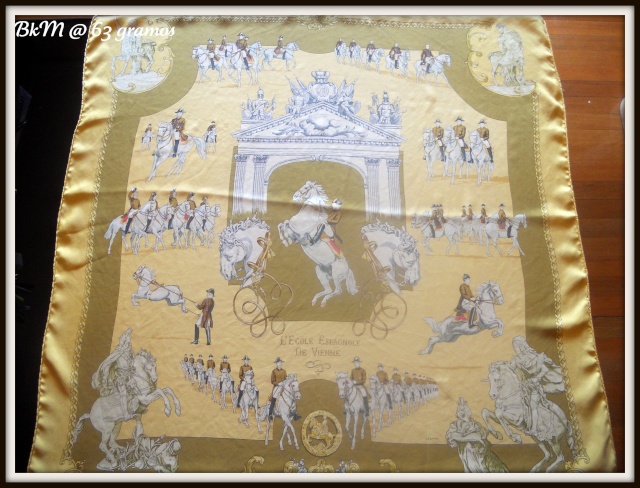

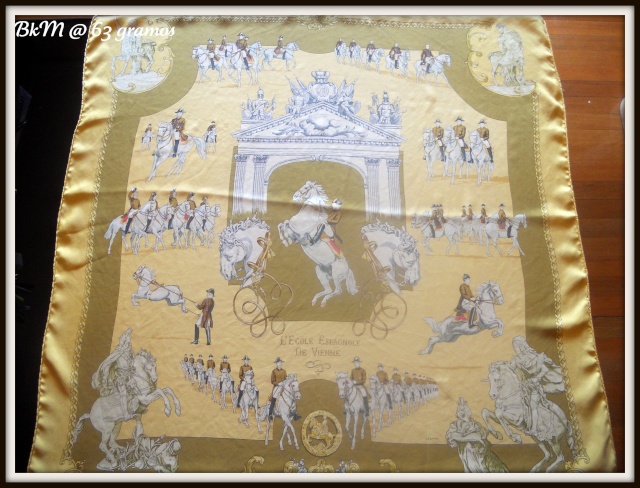

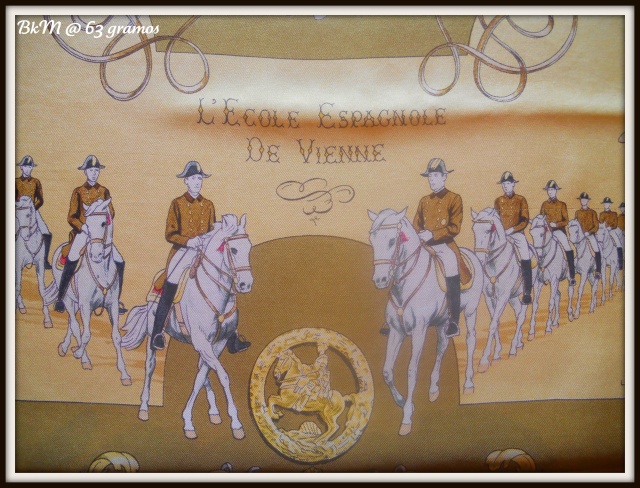

PHILIPPE LEDOUX V: L'Ecole Espagnole de Vienne

PHILIPPE LEDOUX V L'Ecole Espagnole de Vienne

Philippe Ledoux

First Issue: unknown.

Catalogued: 4B

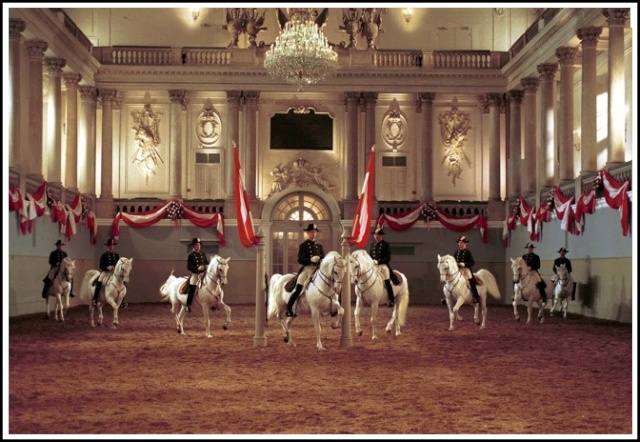

In 1729 Emperor Charles VI commissioned the architect Josef Emanuel Fischer von Erlach to build the magnificent Winter Riding School in the Hofburg Palace; it was completed in 1735. A portrait of the monarch graces the splendid baroque hall in which the riders of the Spanish Riding School train their Lipizzaner stallions and show off their skills to an international audience during the public performances.

The budding rider has to overcome many challenges on his long journey from inexperienced cadet to fully qualified rider, perhaps even to chief rider. Depending on each cadet’s individual talent and personal commitment it takes approx. 4 to 6 years to leave the supervision of the Stable Master and achieve the career jump to the position of an assistant rider.

Philippe Ledoux

First Issue: unknown.

Catalogued: 4B

Yesterday I received a scarf that I'd been looking for for a long time. Unfortunately, it wasn't in great condition but I carefully washed and ironed her (thank you Lily for your advice on this subject), removed the appalling care tag which was falling apart and... voilá! she's become one of my most beloved jewels! Let me present a brief profile of this beauty!

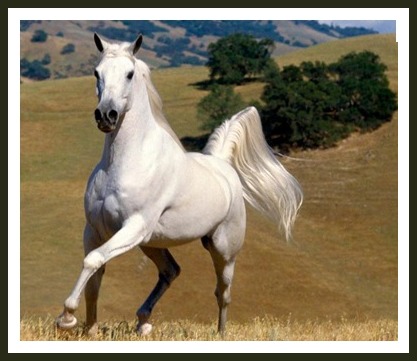

The Spanish Riding School of Vienne, a significant part of Austria’s cultural heritage, is not only the oldest riding academy in the world, it is also the only one where the High School of Classical Horsemanship has been cherished and maintained for over 430 years.

The School takes the Spanish part of its name from the horses which originated from the Iberian Peninsula during the 16th century and which were considered especially noble, spirited and willing and suited for the art of classical horsemanship. Today’s Lipizzaner stallions are the descendants of this proud Spanish breed, a cross between Spanish, Arabian and Berber horses, and they delight horse lovers from all over the world with their performances.

The Spanish Riding School of Vienne, a significant part of Austria’s cultural heritage, is not only the oldest riding academy in the world, it is also the only one where the High School of Classical Horsemanship has been cherished and maintained for over 430 years.

The School takes the Spanish part of its name from the horses which originated from the Iberian Peninsula during the 16th century and which were considered especially noble, spirited and willing and suited for the art of classical horsemanship. Today’s Lipizzaner stallions are the descendants of this proud Spanish breed, a cross between Spanish, Arabian and Berber horses, and they delight horse lovers from all over the world with their performances.

In 1729 Emperor Charles VI commissioned the architect Josef Emanuel Fischer von Erlach to build the magnificent Winter Riding School in the Hofburg Palace; it was completed in 1735. A portrait of the monarch graces the splendid baroque hall in which the riders of the Spanish Riding School train their Lipizzaner stallions and show off their skills to an international audience during the public performances.

As usual, Philippe Ledoux knew how to capture the essence of both the architecture and the show, the equine figures are wonderful, the sense of movement and elegance are impeccable.

The budding rider has to overcome many challenges on his long journey from inexperienced cadet to fully qualified rider, perhaps even to chief rider. Depending on each cadet’s individual talent and personal commitment it takes approx. 4 to 6 years to leave the supervision of the Stable Master and achieve the career jump to the position of an assistant rider.

A cadet’s early years are spent learning not only proper horse care and maintenance, but also the correct handling of all the equipment: saddles, bridles, everything needs to be painstakingly cleaned, neatly stored and properly used.

It takes around 8 to 12 years to successfully achieve the status of a fully qualified Rider, years in which many give up and only the very best persevere.

It takes around 8 to 12 years to successfully achieve the status of a fully qualified Rider, years in which many give up and only the very best persevere.

The prestigious Spanish Riding School, for centuries a bastion of masculinity, is modernizing. Recently, the 436-year-old institution officially presented its first female riders-in-training. Congratulations!!!!

Riders of the Spanish Riding School wear the traditional brown coat, hat bicornis, white pants, white gloves and black suede boots. This style of clothing empire has long been the uniform of the school and has remained unchanged for two centuries.

The Imperial Summer Festival is a celebration in and around the Spanish Riding School, which gives life and color to the summer in Vienna. It is a wonderful show that promotes and enables the Spanish Riding School to open its doors to locals and tourists and at the same time breathe life into the festivities, while reviving the ancient traditions of Vienna.

Dear Holsby shared a picture of a Lipizzaner with me and kindly accepted that I posted it here, it's called Levade - Spanische Reitschule, it was made by Augarten porcelain factory in Wien. Thank you so much, dear friend!

**********************************************

Saturday, April 21, 2012

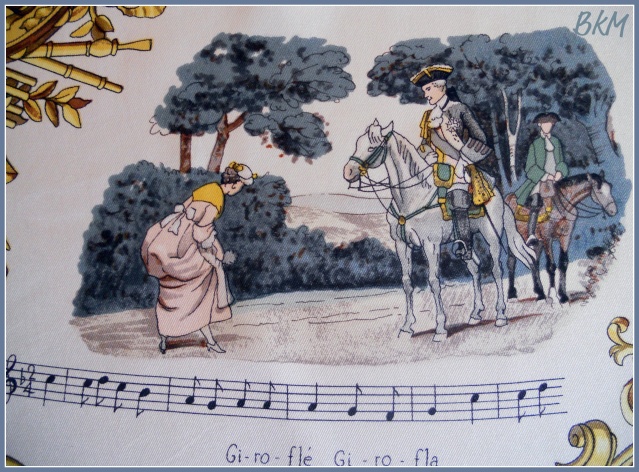

PHILIPPE LEDOUX VI: CHANSONS DE FRANCE

PHILIPPE LEDOUX: CHANSONS DE FRANCE

Philippe Ledoux

First issued: 1970

Other versions: Special Edition Gavroche (date unknown)

Philippe Ledoux

First issued: 1970

Other versions: Special Edition Gavroche (date unknown)

Chansons de France is a classic scarf designed by my most admired Hermès artist, Philippe Ledoux. It's very sought after, rare and difficult to find nowadays and it normally gets very high prices in auctions.

It depicts most of the typical elements of Ledoux's work: minute detail in human figures, architectural elements, elaborate ornaments and historical aspects.

The title of the scarf is shown in the center of a gilded rococo frame:

It depicts most of the typical elements of Ledoux's work: minute detail in human figures, architectural elements, elaborate ornaments and historical aspects.

The title of the scarf is shown in the center of a gilded rococo frame:

The corners of the scarf feature four elaborate ornaments with a riot of decorative elements: Flowers and other vegetal decoration, musical instruments, palm leaves, cherubs, ribbon, scrolls and so on, all of them characteristic elements of the Rococo Style. Rococo (pronounced /rəˈkoʊkoʊ/) took place in the early part of the 18th century in Paris as a reaction against the grandeur, symmetry and strict regulations of the Baroque. Its main features are a strong usage of asymmetrical designs, curves, gold and creamy, pastel-like colors.

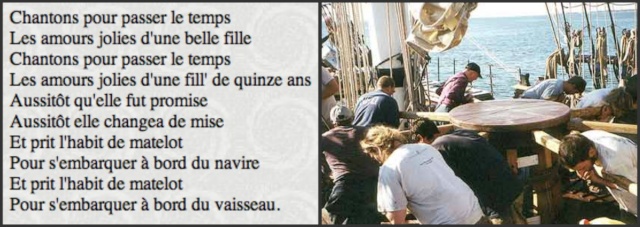

The theme of the scarf is the traditional Chanson, which is in general any lyric-driven French song, usually polyphonic and secular. A singer specialising in chansons is known as a"chanteur" (male) or "chanteuse" (female); a collection of chansons, especially from the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, is known as a "chansonnier". French solo song developed in the late 16th century. Another offshoot of chanson called chanson réaliste (realist song), was a popular musical genre in France, primarily from the 1880s until the end of World War II. Born of the cafés-concerts and cabarets of the Montmartre district of Paris and influenced by literary realism and the naturalist movements in literature and theatre, chanson réaliste was a musical style which was mainly performed by women and dealt with the lives of Paris's poor and working class.

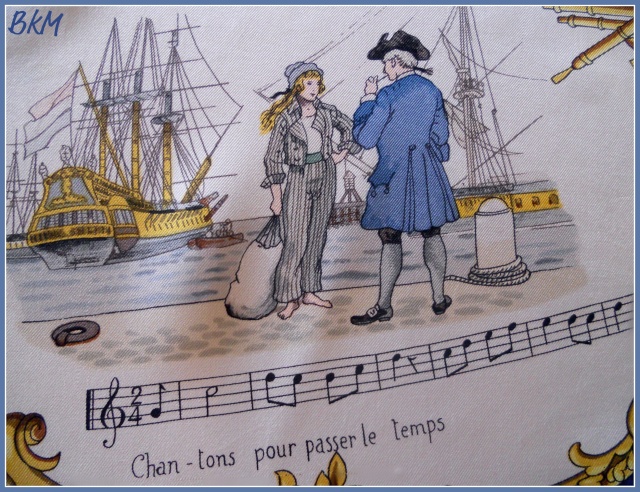

There are twelve vignettes displayed in a circular pattern around the central medallion, all of them are accompanied by a fragment of its score.

Beginning from the bottom left to the right:

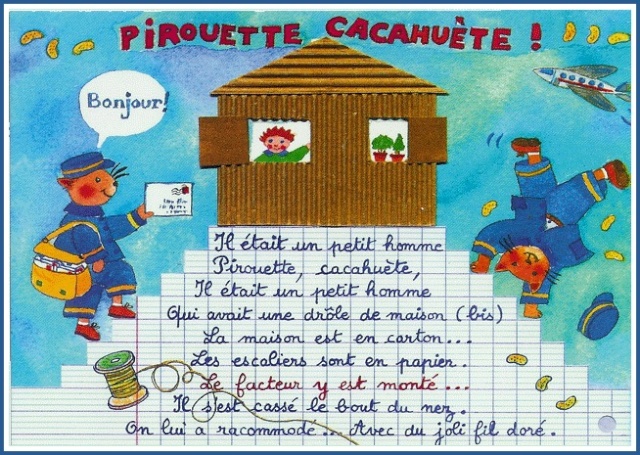

Dansons le Capucine, a circle game song:

There are twelve vignettes displayed in a circular pattern around the central medallion, all of them are accompanied by a fragment of its score.

Beginning from the bottom left to the right:

Dansons le Capucine, a circle game song:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.